Dragon Family Photo

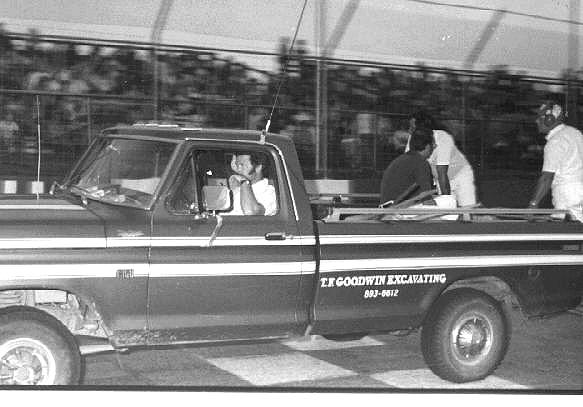

Johnny Bourgeois [far right] and the kitty litter crew could be really fussy when the situation called for it. Below – Jack Paradee, shown here with driver Clem Despault.

BILL'S

[Somewhat] WEEKLY COLUMN/BLOG PAGE

BILL’S BACK IN TIME

By Bill Ladabouche

IT’S WHO YA KNOW AND OTHER THINGS

Fabled Canadian stock car star Jean – Paul Cabana is living proof that, no matter how many tens of thousands of people you know and who know you, you sometimes have to know the right people or you still end up out in the cold, so to speak. In this case, we are talking about a very select group of people known as race track personnel.

When I was preparing Beaver Dragon’s book, he used to love to relate the story of how more than half of the original staff of the Catamount Stadium track were townspeople from Milton, Vermont – Dragon’s home town. In addition to one of the original owners, John Campbell, Sr., a number of other folks had secured jobs at Catamount in the early days of that star – crossed oval.

Dragon Family Photo

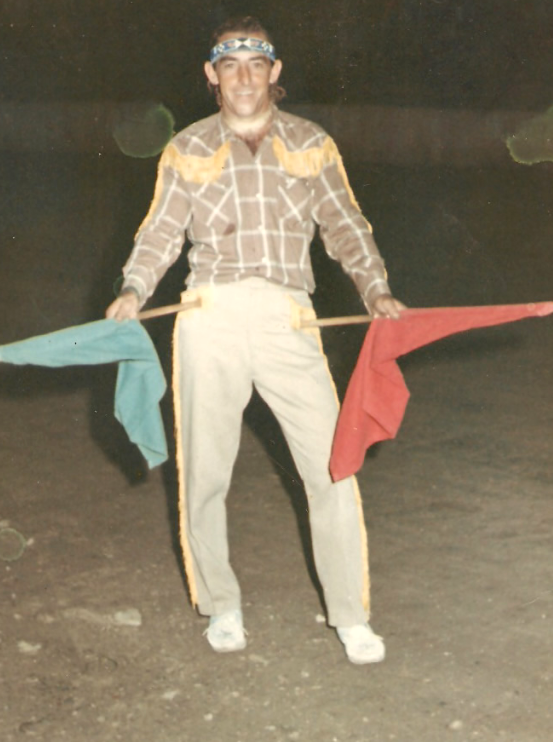

Johnny Bourgeois [far right] and the

kitty litter crew could be really fussy when the situation called for it. Below

– Jack Paradee, shown here with driver Clem Despault.

Courtesy of Chris Companion

Johnny Bourgeois, a burly WWII veteran and Texaco dealer in town, had been like a second father to Beaver Dragon. Johnny ended up more or less in charge of the “kitty litter crew”, a very effective little team of track clean – up personnel. Bourgeois’ brother – in – law, Frederick “Jack” Paradee, was one of the track’s flaggers. Paradee, who sometimes delivered heating oil for Bourgeois and sometimes was a stereotypical small – town policeman [open necked uniform shirt, big belly, and all] was the starter I saw on my first trip to Catamount wearing a necktie. Don Bradley, who lived across the road from the track, was in charge of the concession stands.

Cabana, who won the first and last races in the history of Catamount, was a lightning rod in the charged atmosphere that had developed among rival fans when Milton’s two Dragon brothers ascended to a level of excellence that could easily keep pace with the successful and well – financed racing operations of Cabana [then from Beloeil, QU] and his mentor, the older Andre Manny, from Laval des Rapides, QU.

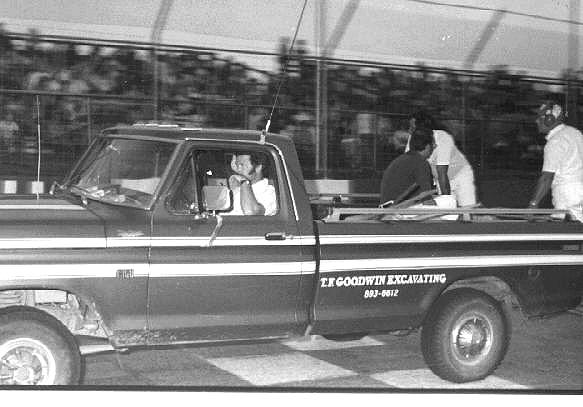

Courtesy of Mr. Chevy Black

Jean – Paul Cabana, shown here with

his first late model sportsman at Catamount in 1971, immediately became a

polarizing

force among the spectators. Below – Jack Paradee and Cabana, in a less

contentious moment, at Catamount.

Courtesy of Cho Lee

Huge shouting matches and numerous bets were exchanged in the fourth turn section of the Catamount grandstands, usually brought on by some over – dressed Canadian with a wad of multi – colored Canadian money held high in the air. One loud yell of “Caw – baw – nah !!!!” is all it would take to start things off every Saturday night in Turn 4.

To return to the point, Beaver delights in telling the story of how, when there would be a caution at Catamount, the time necessary to remedy the situation that brought out the yellow flag would vary greatly, depending on the situation. I don’t mean how bad the accident was; I mean WHO happened to be pitting during that caution. If the yellow flew, and Cabana headed down the pit ramp for adjustment or tire changes, the kitty litter boys were a model of orchestrated, speedy, perfection; and Paradee, waiting, poised with the green flag, would get that race back under motion as soon as possible. After all, did we want to keep the fans waiting ?

Courtesy of Rich Palmer

A Beaver Dragon pit stop somewhere in

1979. If this was at Catamount, it could take a while; if it was in Quebec –

better hurry up, boys ! Below – Butch Lindley, shown at speed at Catamount

around 1976, better have a fast crew.

Denis LaChance Photo

Then there was a Beaver or Bobby Dragon caution. The 75 or the 71 would limp down the pit ramp, and tremendous attention would be given to EVERY speck of anything on that third – mile track surface. One could never be too careful about the safety of those brave competitors on the track. Objects found on the track would be examined and then the finder would mysteriously overthrow the safety truck necessitating the vehicle to slowly back up and retrieve the errant object. Paradee, would often not notice that the crew was done and then make very sure the lineup was correct before giving the field one more caution lap and re – starting. A pit crew of blind men with missing fingers could have had a car back out on the track by then.

Now, if this seems dreadfully unfair to poor Cabana [and there was nothing ever poor about Cabana], consider notes I took from a 2000 interview someone named John Walker did with Jean – Paul about racing North of the border. The one – time drag strip at St Pie, QU known as Sanair had branched out to building a very flat, third – mile paved track on the other side of the massive grandstands on Jacques Guertain’s property. The short – lived flat track was to occupy the Wednesday night slot on Northern NASCAR’s ambitious, five – track summer weekly racing schedule. Needless to say, it did not last long [too grueling].

Courtesy of Pascal Cote

Jean – Paul Cabana, posing in

friendly territory, somewhere in Quebec . SUrrounded by supporters and with

Canadiens

star Jean Beliveau, he is baccked up by promoter Andre Beaudry of ACAQ. Below -

A 1972 late model

field lines up at Quebec Moderne Speedway, a place Cabana could catch a break.

Jean Dessureault Photo

At any rate, Cabana’s long – time friend and sponsor, J.E. Fortin ended up driving the pace car at Sanair. [He probably furnished the pace car to the track, or something like that]. Cabana put it this way in his interview, laughing as he said it: “I would pit the race car, you know, and the pace car would go around the track vey, very slow. But, if Lindley [Butch] pitted, we would get going around very fast and we would turn off the radio because Ken [Squier] would get very mad.” I imagine the Dragons got the same treatment, or worse.

NASCAR was probably not all together in the dark about these machinations on both sides of the border. They were very good at “finding debris” on a race track when one particular driver was stinking up a show by running away with the race. It was just particularly funny because both ends of that story involved the personable Cabana, who loves to tell these kinds of stories to this day.

Ladabouche Photo

The actual C.V. Elms pit stop, that

night, at Bear Ridge. Below – Maybe Ridge regular Herbie Gray might have gotten

a similar

break – after all, he supposedly owned some of the property there.

Courtesy of Cho Lee

I saw one of the longest caution periods in the history of mankind [and that includes one pit stop by Messala during the Roman chariot race involving Ben Hur which I witnessed as a lad] at Bear Ridge Speedway in the late 1970’s. This was around the time the real coupes were in their last hurrah there, and a few Gremlin, six – cylinder modifieds were beginning to spring up. At that time, Elms, Sr. [Chuck] was still around and Butch [CV Elms II] was still driving his white coupe with the red number 6.

The feature event had begun, that night, and there was a pileup on the cramped fifth – mile dirt oval. In came the Elms coupe, limping on a flat tire. There was chaos in the dimly – lit pit area, as everyone scattered to let the track owner find his pit. There was no immediate problem on the track that I could see, but the field just circled the tiny, dusty oval, over and over again, as the hastily – assembled tire crew struggled with a hand – powered X lug wrench on Elm’s rear slick. Finally, as the field seemed to be giving the one – to – go sign, the coupe flew out onto the track. I doubt Brother Eastman, the track’s other big star would have had so many caution laps.

Ely Family Photo

Chuck Ely in a different Casper car,

safely away from Fairmont Speedway. Below – Ely brother – in – law, Butch Jelley

in Victory Lane with Rumpf [right] and Frye [background].

Courtesy of the LaFond Family

Giving or not giving drivers a break under caution has fueled fiery outbusts for decades. I can recall a time at the old Fairmont Speedway in Fair Haven wherein the Lebanon Valley regular Chuck Ely had pitted with a neat 1956 Ford Crown Victoria. Ely’s #5 Ford, familiarly known as the Casper the Ghost car, had failed to make it back out as the race was being re-started.

Incensed, Ely pulled out onto the track and proceeded to park on the front stretch. Starter Danny Rumpf, of course, had to throw the yellow and try to reason with the furious Ely, a sign painter and photographer as well as race driver. The angry Ely apparently painted a pretty clear sign for Rumpf and fellow official, the hard – nosed Jim Frye. His butt was tossed from the track for the day. Beside himself by now, Ely drove the car in angry circles through the pits and back onto the track several times, with bystanders ducking for cover. He actually rolled the Ford once, coming right back on his wheels. They nabbed him before he could restart it. Lots of excitement for spectators !

Courtesy of the LaFond Family

The Unbeatable Lennie Wood, with car

owner John Maguire, during his win streak year of 1965 at Fairmont. Promoter CJ

Richards is at left and Rumpf is at right.

Ely pointed out, none too politely, how track regular The Unbeatable Lennie Wood had gotten a longer pit time just about a a race before. This may have inspired Ely to come back ,at the end of the season, and put an end to the win streak of Wood. The whole incident might have been the most exciting part of an otherwise somewhat unremarkable afternoon of racing.

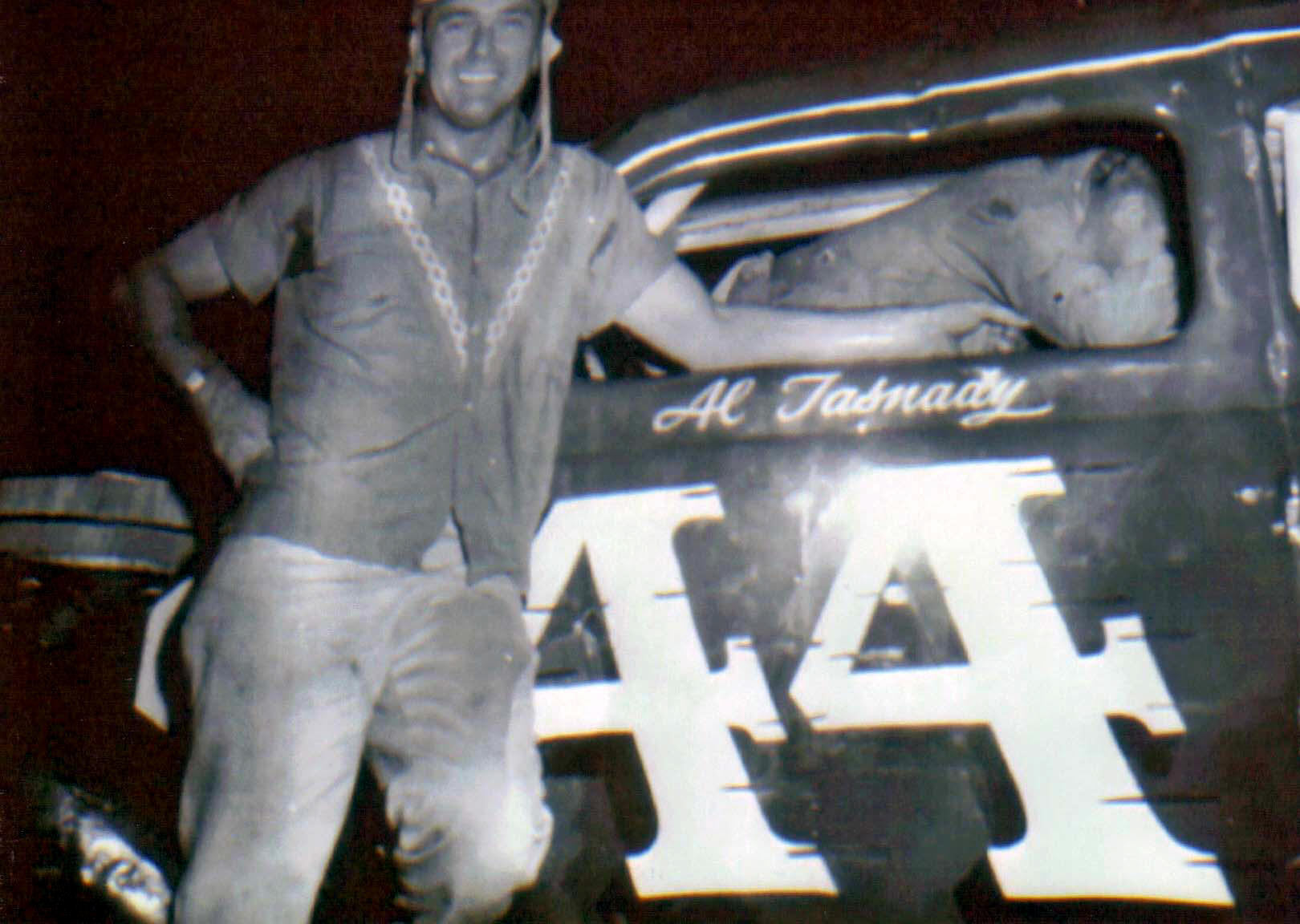

John Snyder recently told a similar tale about goings – on at the old Flemington Speedway [Flemington Fairgrounds, NJ] in the 1960's. It seems that certain drivers had made a bigger hit with officials and competitors than others. One who had apparently not was the transplanted Floridian Wily Will Cagle. Snyder relates how, one particular night, there was a pretty good wreck involving everyones' favorite, Al Tasnady.

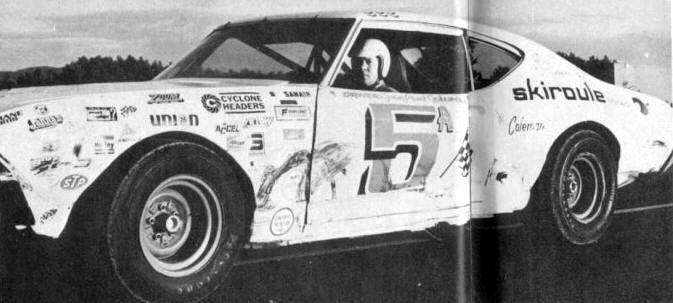

Courtesy of CJ Richards

The Wily One, in a Devil's Bowl

photo, where he stole off with most of the best prize money for several seasons.

Below – Al Tasnady, with an early Dick Cozze 44.

Courtesy of John Snyder

Tasnady's bent car [could have been the Cozze 44, the Piscopo 39, or the Deasey 707] was towed into the pits whereupon people from nay crews set upon it to return it ot action. The Flemington officials found many important tasks to keep the race from re-starting. According to Snyder, they practically repainted the concession stands. Finally, Taz made it back out “just in time'.

A little later another accident re-arranged the 24 of Cagle. The ass end of the white coupe was barely off the track when the starter, Tex Enright, signaled one to go and flagged off the restart. Incensed, Cagle finally came back out and proceeded to park his car in the way on the track, causing another pileup. Will was summarily fined and suspended from the track rather stiffly. Snyder thinks this is about when Cagle began preying upon New York and Vermont tracks further to the north [which he made a living off for years].

Source Unknown

Let 'em go, Tex !

The length of caution periods has been of function of track location and local connection for probably as long as stock car racing has been going. Is it really any different than the grounds crew of a major league team heavily watering down the infield if the opposing team has a fast base stealer? I think not. Thunder Road now has a policy I like: we will hold the race, within reason, until you are out of the pits or signal you are done for the race. Works for me – but it lacks the drama and outrage of the older days.

Please email me if you have any photos to lend me or information and corrections I could benefit from. Please do not submit anything you are not willing to allow me to use on my website - and thanks. Email is: wladabou@comcast.net . For those who still don’t like computers - my regular address is: Bill Ladabouche, 23 York Street, Swanton, Vermont 05488.

AS ALWAYS, DON’T FORGET TO CHECK OUT MY WEBSITE

www.catamountstadium.com

Return to the Main Page

Return to the Main News Page

Return to the All Links Page

Return to the Weekly Blog Links Page