BILL'S

[Somewhat] WEEKLY COLUMN/BLOG PAGE

DON'T SPARE THE

HORSES

[ I want to give full credit for most of the material in the first part of this article to the authors of the Fonda book. They, indeed, did their homework on a topic that offers very little information.]

It used to be a standard line in old movies about the olden days to have some king or rich guy get into a fancy carriage and yell out, “To the castle, Carruthers, and don't spare the horses !” This pretty much suggested he wanted haste and he didn't particularly care about the toll it took on his minions or horses.

While this is not a direct parallel to the two subjects of my writing this time, it still has a familiar ring to it. We have two cases where in overly – ambitious planning without much attention paid to reality, definitely stressed the minions and their modes of transport at the time.

Clip Art Source

Unknown

Don't spare the horse, Carruthers !

Our first [and earlier] case has to do with a big – thinking promoter and thrill show operator from New York by the name of Jack Kochman. I recall seeing the Jack Kochman Hell Drivers put on a show at the Vermont State Fair in Rutland, Vermont right around 1957. The show had pretty much the standard auto thrill show fare with drivers wheeling new 1957, Mopars and a few guys crashing junkers in various manners.

What I recall from that afternoon was one particular driver named Bobo Canupp, who managed to roll one of the new cars off a ramp. I remember seeing him standing there, his face contorted with anger. In retrospect, Kochman probably made him pay for the damage. However, it is not the Lucky Teeter stuff that we are looking at Kochman for.

Getty Images

No matter what the year, Kochman liked his

Mopars. Below – A typical moonshine runner and

his typical mode of transport. Looks like an early modified.

From Pinterest

In 1947, the sport of stock car racing [barring jalopies] was just being born. It is somewhat overdone [but yet true] that the booze – running moonshiners of the Deep South had really sort of invented the sport, having already taken the common American passenger car and modified it into a fast, powerful, well – handling piece of equipment to outrun government “revenuers” who pursued them with the intent of stopping the un – licensed and therefore untaxable production of corn whiskey.

When those good ol' boys started to stage races to decide who had built the best cars powered by the hottest “mills', the sport of stock car racing was born. Early efforts were being made to organize the new sport by visionaries like Big Bill France, and Jack Kochman [who already running his thrill shows] had witnessed an event organized by France and run at the Langhorne track in Pennsylvania. Immediately, Kochman decided to form the Speed Corporation of America, using Southern – style modified stock cars. Backed by NYC venture capitalists, he came up with six northeastern fairgrounds venues which would form a circuit on a weekly basis.

Getty Images

Modifieds line up for the modified stock car race

at Langhorne

in 1947. The bodies were largely untouched but the engines ?

Another story ! Below - Jack Kochman.

Fortune City.com Photo

Racing would commence in 1948. While this was going on, NASCAR was forming down South. Kochman would immediately arrange for a NASCAR sanction for his “stock cars”, under which rules would allow for some modificatios to motors. [Hence, the terms “modifieds” stuck.] The tracks involved were Allentown, PA; Kingston, RI; Lewiston, ME; Fonda, NY; Palmyra, NY; and Dover, NJ.

The strenuous and unrealistic schedule would spell trouble for the group, affecting car counts and eventually killing off the idea. Allentown on Tuesday night; 5 hours to Kingston for Wednesday; a number of hours up to Maine for Thursday night; 10 hours to get to Fonda for Fridays; four hours to Palmyra; and then an all – night drive to get to Dover for Sunday. This was to go on, officials and teams alike, for four months.

Historic Aerials.Com

The Lewiston, Maine fairgrounds were well up into

Maine – with no

Maine Turnpike at the time. Below – The Wayne County fairgrounds in

Palmyra, NY were square in the middle town – but many miles

west of Syracuse. Farther Below – Wally Campbell at the Palmyra venue in

1948.

Historic Aerials,Com

Wally Campbell Collection via Flemke.Com

Southern star Frank Munday stated that the schedule was brutal. People on each team would take turns driving; seldom did they get to stay in a motel or even get a regular meal or bath. Munday said that, after a fashion, no one could stand the smell of anyone else. It wasn't much easier for the team of officials: announcer, Jimmy Roberts; flagger, Craig Mellinger; or chief steward Bob Sall.

Things went wrong right off the bat. Fonda was to have the first show on May 21, 1948, which was canceled by rain. The following week, when the make-up show opened, only seven cars showed. A nine car crash at Allentown, road arrests in Maine, and other factors thinned the field, and the show had to be canceled again.

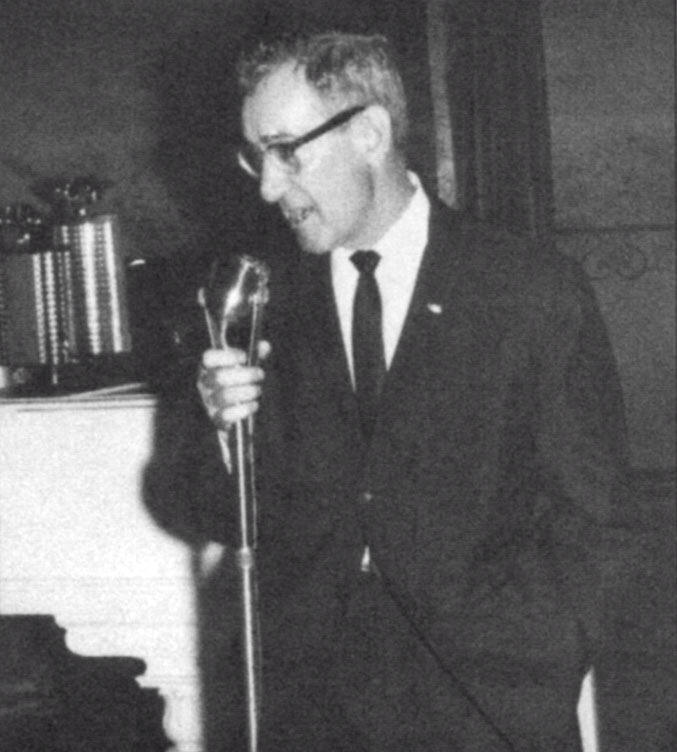

Ed Biitig Collection

Bob Sall, speaking at a banquet a number of years

after his

grueling SCOA experience. Below - Wally Campbell [ctr]

is a winner in 1947, flanked by fellow SCOA sufferers Frankie

Schneider and Tommy Coates of the W.O. Taylor team.

Norm Oakes Photo via Jeff Hardfier and 3 Wide

Fonda finally got in a show – between the raindrops – on June 4, 1948. Frank Munday, Joe Ledegar [LI], and Wally Campbell [NJ] won heats. The class of the circuit was Buddy Shuman, whose car was said to be one of his actual moonshine – running vehicles converted for racing legally. The red, white, and blue alcohol – powered #4 Ford was, by far the fastest one there.

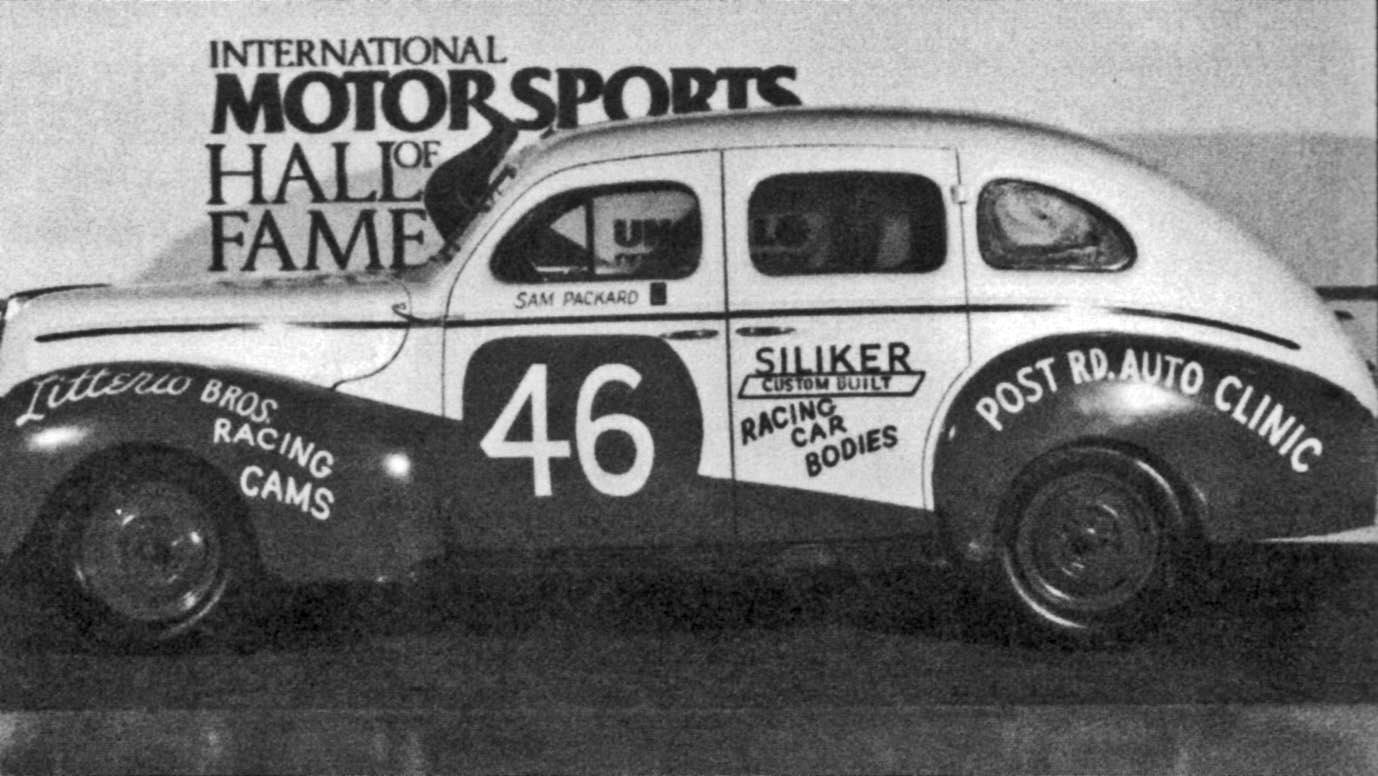

The W.O. Taylor Paterson, NJ – based team of Wally Campbell [90] and Johnny Rogers [89] were second and third. Sammy Packard [RI] was 4th, edging Maine Ken Littlefield. Packard drove a full – sized 4 door Mercury. Florida driver Bill Snowden fielded a brand new #15. The Taylor team also sometimes had a car 91 driven by Tommy Coates.

Samples

Collection Fonda Book

Buddy Shuman relaxes after the win at Fonda. Note

how little

the car is modified for racing. Below – Sammy Packard with

the sedan.

International Motorsports Hall of Fame Photo

The Fonda shows, at least, were supposed to be supplemented by a “hot rod” class – which was basically roadster jalopies from tracks like nearby Canajoharie. I have no usable roster of the modifieds, but – besides the names already mentioned, Ben Cannaziaro, and Ernie Palmer could be added to the list. After a thin showing, the hot rods were eliminated out of the programs.

After only a month, Sammy Packard once said both the equipment and the people were wearing out fast. Strains were also created when sometimes, teams would decide not to flat tow their cars and would simply drive the car to the next venue. Packard missed the June 11 show because his Mercury had blown up driving along in Springfield, MA, coming down from Lewiston, ME.

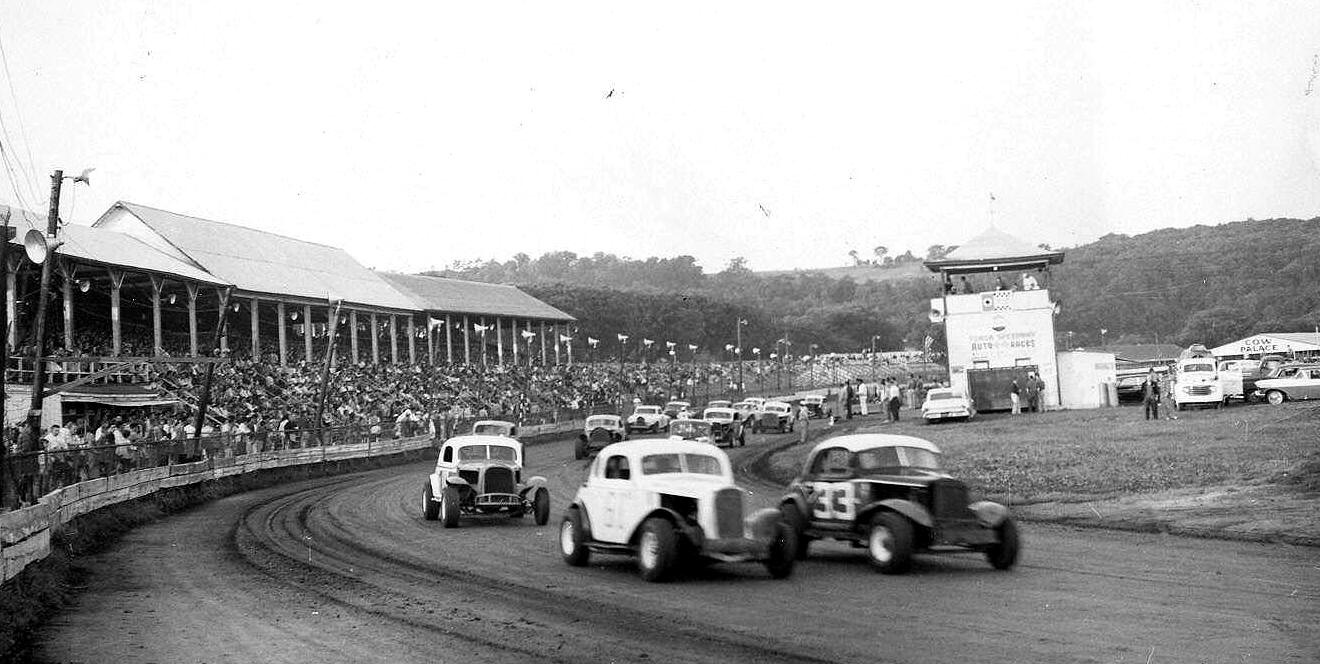

Russ Bergh Photo

A race starts at Fonda in the early '60's.

Kochman's track

barriers and lights are visible. Below - Racing continued

at the Kingston, RI fairgrounds after the Kochman deal

failed. Familiar racer Don Rounds is in the car still on its wheels

[his first car].

Courtesy of Mark Sousa

The Montgomery County venue at Fonda was the first to fall out of the circuit. Kochman soon folded the tents entirely, leaving some of the lighting, guardrails, and other improvements behind at Fonda. Kingston, RI survived, having built up a following of local drivers and fans. Nothing is said about the other places. Fonda would remain in limbo for more than four years. Nothing more was heard of Kochman's idea, although modified racing prospered both in the Northeast and the South.

Our second grand scheme was far less chaotic and more successful than the SCOA, but it still exacted a toll on the participants and had to be pared down. Racing visionary [and crackerjack announcer] Ken Squier had built two tracks in Vermont by 1965 – Thunder Road International Speedbowl [a quarter mile high banked paved oval] and Catamount Stadium, a modern third mile paved track. Having been envisioned as a track for midget racing, Squier had immediately gone over to flat head Ford coupes in 1960, fearing the midgets were too fast on the track to be reasonably safe.

Bob Mackey Photo

via Mike Watts, Sr.

Les King goes to check on a midget that has

crashed at barre,

Vermont's Thunder Road. The little rockets had a hard time

staying on the high – banked quarter mile. Below - This

Roger Rouleau car is typical of the standard entry in the

first years of Thunder Road.

Courtesy of Mark

Austin

Thunder Road would always get fields and crowds, although floundering around for an identity after Catamount opened in 1965 and Squier had brought in NASCAR. Catamount struggled with small fields at first and the Road put up with the new overhead V-8 sportsman cars from New York and Canada only about half a season before sending them off. Catamount would quickly build up fields and become an important stopping – off place in the burgeoning Northeast modified / sportsman racing scene until in 1968, without much warning, it also dumped “the coupes” entirely.

Squier [later joined by the equally – promotional Tom Curley] had a plan. He would live with his rag tag Flying Tiger support class through the 1969 season, upgrading them to limited sportsman cars in 1970. Finally, his two tracks would run full – fledged NASCAR late model sportsman cars, starting light years behind the Southerners in terms of race car development. However, the Northern NASCAR circuit would soon be a magnet for late model teams from southern New England, New York, New Hampshire and Quebec.

Courtesy of Cho

Lee via Mike Watts, Sr.

A field of 15 sportsman coupes was about par for

the

course in early Catamount days. Jean – Paul Cabana,

Andre Manny, Kenny King, Bob Bruno, and Gaston

Desmarais were among those taking green. Future

promoter Tom Curley is said to be in that car #2 in the back.

Below – By 1968, all that was left were Flying Tigers.

Courtesy of Andy

Boright

By 1973, Squier and Curley had come up with a very ambitious plan. The teams would begin to run five times a week at venues ranging from Quebec to southern Vermont. Although Northern NASCAR had skimmed off a lot of the better late model teams from Massachusetts' Norwood Arena, including that track was apparently not in the cards [thank God for the poor teams involved].

The racing teams, almost all of whom were not full – time professional organizations would start off at a third mile flat track on the site of the well – known Sanair drag racing facility in St- Pie, Quebec. Thursdays would at Thunder Road; Fridays, they would be struggling around the crumbling half – mile track at Airborne Park Speedway near Plattsburgh, NY; Catamount got the plum, running its show on Saturday night; and Devil's Bowl Speedway [having paved and recently jumping on board with Northern NASCAR] would use its traditional Sunday night.

Courtesy of Wayne

Bettis

The newly – finished Sanair flat track would

start off the week.

Below – Former NASCAR national champion Rene Charland

was one of many newcomers who did not find Thunder

Road to his liking, as you can see here. [He did this twice

in the same season].

Courtesy of Andy

Boright

It all sounded great until you took into consideration that these were mostly men [and women] who had regular jobs and many of who only had one race car at their disposal. Catamount, Airborne, and Thunder Road were not far from interstate highways, but Devil's Bowl and Sanair were in the middle of nowhere. The season started off with two straight wins by Beaver Dragon – himself not having returned for long from a self – imposed exile from Squier's tracks. Then the grind began to set in. No two tracks were alike, making considerable setup changes [or, in some cases, making heavy use of the backup cars for teams that had them]. Tracks varied from a quarter mile, heavily – banked T Road to half – mile, nearly flat Airborne. And, the cars would come to T Road from a totally flat Sanair track the night before.

Dragon Family

Collection

Beaver Dragon took this home built Chevelle LMS

and

Won the first two races of a very long season. Below -

The John Rosati team attacked the circuit with two

identical cars and a paid crew chief, Fred Rosner.

Ladabouche Photo

Curley and Squier had their established stars by 1973: Beaver and Bob Dragon,

Milton, VT; Ron Barcomb from Winooski; Tom Tiller, from Essex Junction, VT;

Stanley “Stub” Fadden, North Haverhill, NH; John Rosati, Agawam, MA; Dave Dion,

Hudson, NH; Hector LeClair, Fairfax, VT; Robbie Crouch, Georgia, VT; Joey

Kourafas, Stoughton, MA; Jean – Paul Cabana and Andre Manny from Quebec: and a

host of other teams. As I recall, the teams of Barcomb, Rosati, Tiller, and

Cabana were some of the ones with multiple cars.

It didn't take long for the strain of the ambitious tour to start taking a toll on the teams. Many of the cars took on a battered , ratty appearance. Some teams got to where they were sitting out certain races. Drivers like Middlesex, VT's Ron Bettis would have a bad wreck and getting back out to maintain an effort on the whole circuit would temporarily suffer.

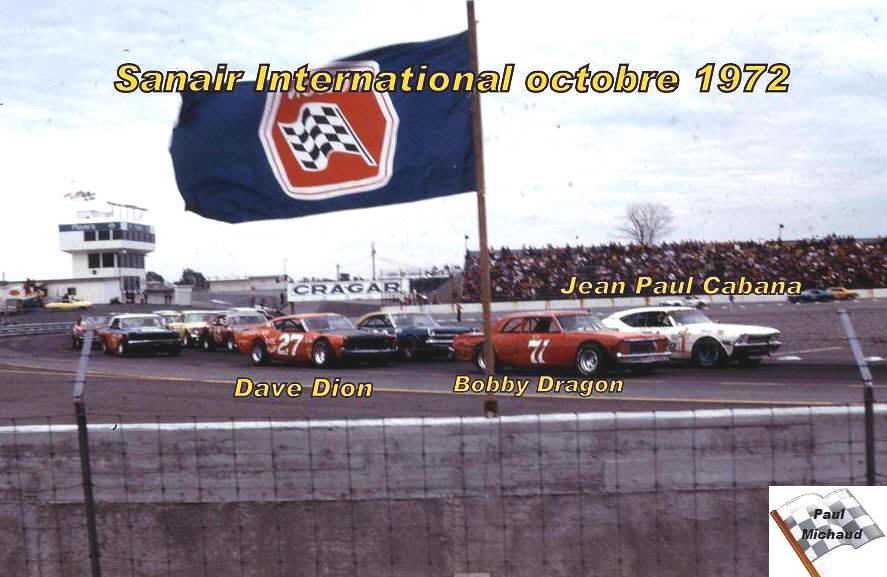

Bob Mackey Photo

via Dave Brown

Bob Dragon's dominant Allison – built Chevelle

shows the

strain of the season as the crew works at Airborne on a

Friday night. Below - This photo, mislabeled as 1972, shows an

impressive front field of Cabana, Bob Dragon, Dion, and Rosati.

Paul Michaud

Photo

Everything was not all hearts and flowers for some of the tracks either. Sanair [named for owner Jacques Guertain's patented system for treating the air in huge poultry barns] was unpopular right off for two reasons: 1.) its earliness in the week and 2.) its completely flat surface [surveyors found there was only a difference of six inches, anywhere looking across the place from one stretch to the other]. So, before the season was anywhere near closing, Sanair dropped out of the weekly schedule.

The other malcontent was Devil's Bowl. For whatever reason, C. J. Richards had paved his beloved clay track in 1971 and – after trying modifieds for a year – had decided to get in on the rapidly – growing Northern NASCAR scene by 1972. He loved his Sunday night time because, before, it had attracted dirt racing teams who didn't have much of anywhere else to run unless they wanted to go all the way near Utica, NY.

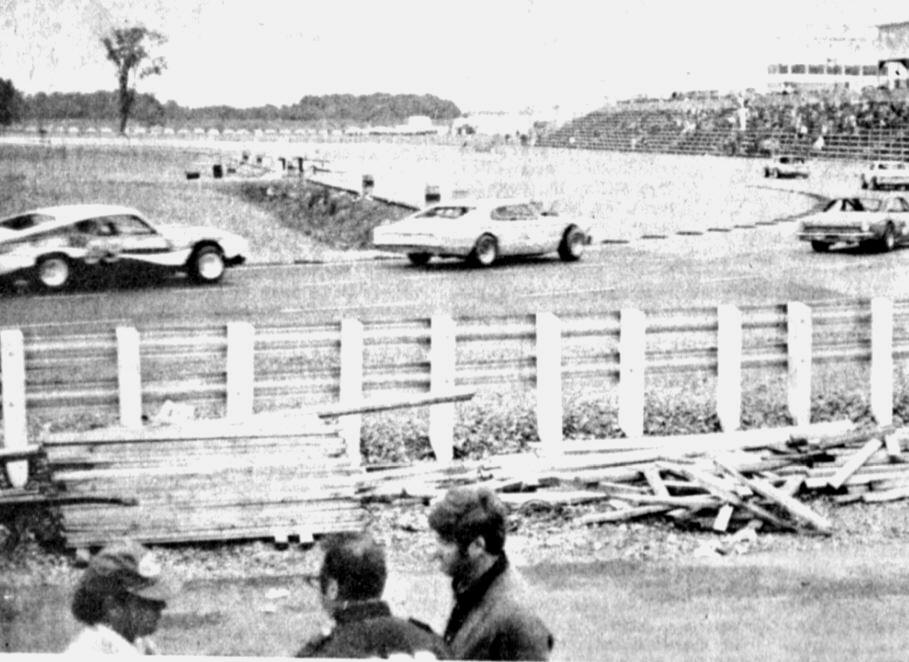

Dick Britain

Photo

Although this is a 1972 of Northern NASCAR at D

Bowl,

many of the same teams competed in 1973; their cars just

didn't look this good by the fifth straight day of racing.

Below - Ron Barcomb's car on the hauler, arrives at

Catamount Stadium. Ever the innovator - that year, he had

a sponsor just for the hauler.

Courtesy of Chris

Companion

However, what happened was not due to lack of interest. By the time the teams had run Sanair on Wednesday, T Road on Thursday, Airborne on Friday, and Catamount on Saturday – many of the cars were out of commission [and sometimes so were the haulers]. If that wasn't bad enough, T Road got to run some Sunday afternoon races, after which the teams were expected to throw everything on the trailer, run a short ways down Interstate 89, cross to the West on back roads through the mountains, hit US Route 4, and arrive at the Bowl often too late for adequate prep or practice. Their performances reflected this, and a few of the lesser teams began to realize that, if they skipped races and concentrated on the Bowl, they could look like headliners.

One week, the circuit had attracted guest star Tiny Lund, who was running his own late mode sportsman Chevelle with the circuit regulars. Besides finding out his rough driving would get answered in kind, Lund's team found themselves rjusing [along with everyone else] to get loaded up and headed down to Devil's Bowl. They hurried so much, they ended up losing an expensive, special racing jack somewhere on the interstate that day. One of the local teams hit the jackpot.

Bob Frazer Photo

Source Unknown

C.J. Richards had his former regulars like

Wilton, NY's

John Peoples, who would make sure he made it to D Bowl.

Below – Dewayne “Tiny” Lund found his second visit up

North in 1973 a little more hectic than the first one.

Bob Doyle Photo

via Cho Lee

After that insane 1973 season, Devil's Bowl dropped out, Airborne was to follow during the 1974 season, Sanair was already gone. And – suddenly - things got a lot simpler for the Northern NASCAR teams. This would, at some point in the future, lead to conception of Tom Curley's “beer tours”, whereby the two Vermont tracks stopped running weekly shows and races were held at a wide range of Northeastern, New York, Canadian venues.

I recall Stock Car Racing magazine running an article on that crazy five – track schedule. It was not complimentary. They were very tongue in cheek about the sensibility of trying such a schedule and they didn't choose to use some of the more appealing photographs that could have been available. So, the Speed Corporation of America, 1948 and the Northern NASCAR circuit of 1973 both stumbled under the weight of schedules that swere too ambitious to be realistic. Even today, most teams – no matter how many resources they had] would take anything like either of those schedules. Wouldn't one of those 1948 modified teams have loved a double stacker with a living room ?

Bob Frazer Photo

via the LaFond Family

Even on race five of a long week, life goes on.

Ron Barcomb's uncle,

Ernie [himself a former driver] sees the tire man for mounting.

Barcomb was a Firestone man then, and the tire truck sold

Goodyears. That must have been interesting.

Please email me at wladabou@comcast.net if you have any photos to lend me or information and corrections I could benefit from. Please do not submit anything you are not willing to allow me to use on my website - and thanks. For those who still don’t like computers - my regular address is: Bill Ladabouche, 23 York Street, Swanton, Vermont 05488.

AS ALWAYS, DON’T FORGET TO CHECK OUT THE

REST OF MY WEBSITE:

www.catamountstadium.com

Return to the Main Page

Return to the Main News Page

Return to the All Links Page

Return to the Weekly Blog Links Page