This poor photo of Mick Wilcox and his Flying Tiger is the only good shot of the tree house

over his right shoulder. [Courtesy of Lloyd Gilbert]

THE

BILL'S BACK IN TIME COLUMN PAGE

Copies of my column in Mark Thomas' "Racin'

Paper"

BILL’S BACK IN TIME

By Bill Ladabouche

Site Column #75 from My

Column 90

INTERESTING CATAMOUNT STORIES

Catamount Stadium had a reasonably long lifespan, if you compare it to tracks Fairmont Speedway, Arundel Speedway, Colchester Raceway, or even Stateline Speedway; and not so long if you look at the Fondas, the Staffords, the Claremonts, and the Oxford Plains of the racing world. Life span notwithstanding, Catamount had its share of little, anecdotal stories and events that helped shape its lore and ensure its niche in racing history.

One of the first such stories is that of the Sibley boys’ tree house. The Sibleys lived on US Route 7, to the immediate east of the Catamount property. Mr. Sibley, I believe, worked on the Town of Milton Road Department with Beaver Dragon – and the Sibley kids were excited at the prospect of seeing Beaver in action at the new track next door.

This poor photo of Mick

Wilcox and his Flying Tiger is the only good shot of the tree house

over his right shoulder. [Courtesy of Lloyd Gilbert]

Not long after the track at begun operation, it dawned on the Sibley boys that they had a tall tree on their property that extended over that corrugated metal fence that surrounded Catamount’s pits and which served to block view into the track from anywhere to the east. It didn’t seem fair that folks over the north boundary – near Camp Pre-Cast Concrete, could climb onto a hay wagon located by the fence and watch the action for free.

So, construction in the area began, all over again, as the eighth wonder of the world, the infamous Catamount tree house began to take shape. Once thrown together, the structure offered a pretty decent view, according to Joan Sibley, who was allowed access to this otherwise all-male sanctuary. Things went swimmingly well for that year and most of the next, until an errant racing wheel nearly made it up the tree house.

Marcel Godard, in probably

was his tree – climbing coupe. Courtesy of John Rock]

Later, according to what I have been told, Marcel Godard, the racing beautician or whatever he was, nearly climbed the tree [on which sat the tree house] with his white number 4 sportsman coupe. These two events made the Catamount management very uncomfortable about the birds perched in the tree right outside their fences. They then sought to talk Mr. Sibley into keeping the kids out of the tree house on days when there were racing programs. For the record, however, most of the Sibley kids did end up with jobs at the race for as long as they wanted them.

Another story centers around fire. While Catamount never saw a fatality in its years of operation, it did see two serious fires by 1970. In the first instance, around 1966, a Montreal driver named Ray Forte came down with a beautiful, bright red. 1936 Chevy coupe numbered 90. Forte, a kind of a flaky guy, had driven for other people before with varying degrees of success, but this was his car. In one of the sportsman heats, there was a mixup, and Forte ended up being rear-ended by Jack Anderson, in the #5. The Forte car erupted into flames, and it became immediately apparent that the track did not have the proper fire equipment to deal with an eruption of this magnitude.

What is left of the Ray Forte

coupe is hosed down by Larry Adams as Beaver and Bob Dragon look on,

back by the truck. [Courtesy of Cho Lee]

By the time the local Milton Fire Department had arrived, the Forte coupe was reduced to skeletal remains. Larry Adams, and the few other men he could rouse on a Saturday night, enlisted the helped of on – site fireman Beaver Dragon, and hosed down what was left of the car. About a year or two later, Ron Perry, a Milton driver, had his big old four-door 1957 Chevy Flying Tiger car catch on fire while sitting on the front stretch, waiting to begin the parade lap for the feature. Again, there was nothing left by the time the local volunteers got there, and Johnny Bourgeois’ wrecker got to remove a melted hulk from in front of the uneasy spectators, one of whom was a man with enough influence to concern the Vermont State Racing Commission.

With the Commission losing patience, Ken Squier and the rest of the track management went out and bought a big, white crew cab pickup truck which carried about the biggest red fire extinguisher I have ever seen. For years, the truck appeared in the infield for every race event at Catamount. Rumors swirled as to whether the giant extinguisher was always charged and operational, but its mere presence seemed reassuring to most in attendance.

Then there was the infamous pit bleacher incident. When Catamount was being constructed in 1965, one of the founding fathers made arrangements to purchase the stands that had been used for the President Lyndon B. Johnson inaugural festivities in Washington, D.C. that January. These stands were re-erected on an asphalt base at the state-of-the-art new track. One section was placed in the pits. Everything was fine for years.

Around 1976 or 1977, during a particularly hot Saturday night during an unusually hot summer, crews had assembled on the pit bleachers to watch the upcoming qualifying heats. Dozens of men and women had climbed into those stands, located just off the pit access ramp, by turn one. As one heat was coming down to take the green, we all felt a small tremor of sorts, and the stands we were on kind of settled down – about a foot.

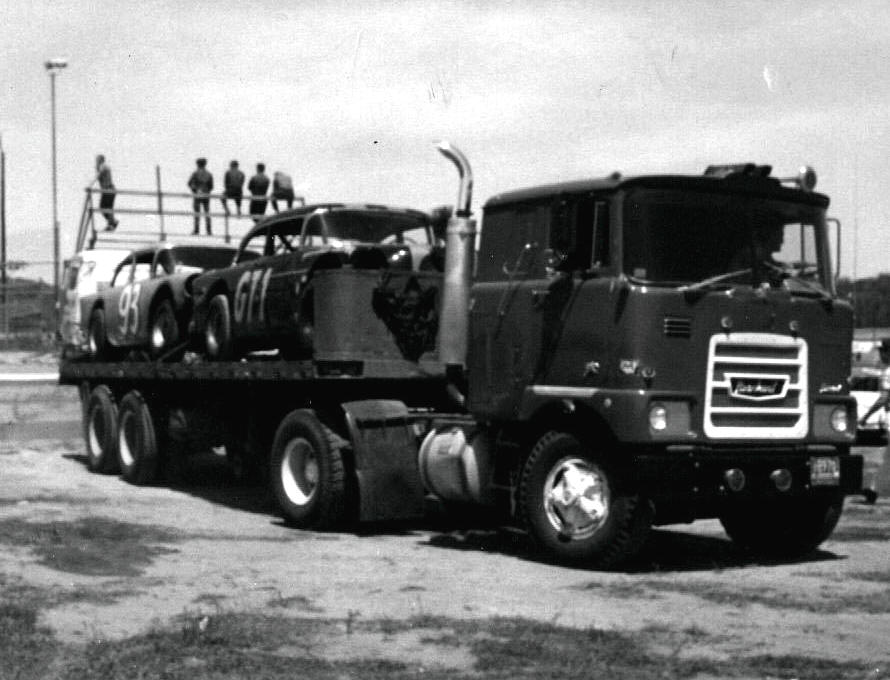

The Catamount pit bleachers

can be seen here, behind the truck unloading cars. [Courtesy of Cho Lee]

One lone voice said “Oh, shit !” In the next instant, the bleachers sort of settled and sort of fell, much like an overheated senior in a steamy hot gymnasium, halfway through a long graduation speech. We really swooned to the ground, more than we crashed.

After a couple of moments of dead silence, the shouts, the moans, and the cussing began to fill the muggy night air, and you could hear footsteps running to us from all directions. I ended up with both legs trapped under the seat in front of me, sitting on the head of one of Bernie Griffith’s crewmen. A voice from below me said, “For God’s sake, don’t fart !” I felt badly for the skinny guy because, at that time, I weighed about 230 pounds. Luckily, guys rushed in to lift me up enough for the Griffith guy to move out from under. It was an hour before we all were able to clear the mess.

One man, who had leapt from the top row of the bleachers, had hurt his back. There were about two more semi-serious injuries, and the rest were people like me – maybe a little sore but not wanting to cause any more trouble than had already happened. Pretty soon, some new stands appeared. We heard that there was a hurried inspection of the main grandstands and it was determined that some were sinking into the hot asphalt, but not at an alarming rate. The heat abated, and so did much mention of the pit bleachers; but not one year goes by that someone doesn’t mention the incident in a conversation about Catamount.

The next story is not a happy one. The Spring Green had become a fixture as the start of the Catamount season, each year. By the 1980’s Catamount was not always running weekly programs, but the April race was still the big ticket. Robbie Crouch, having started at Catamount in 1971, was now up there with the Dragons and Cabana as one of the hottest names in NASCAR North racing. He had top equipment, a great sponsor, and was beginning to amass a win total that would – one day – become the best in the history of the American-Canadian Tour [ the successor program to NASCAR North].

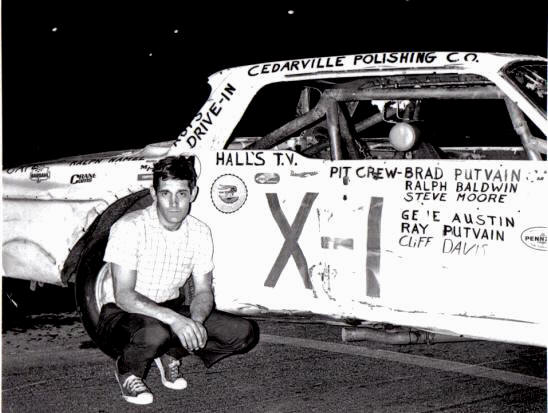

Ricky

Crouch and the car he was to drive at Catamount that year.

[Courtesy of Darrell Rogers and Mark Dean]

In

1986, the circuit was finally to feature a second Crouch [or third, if you count

C.A.]. Younger brother, Ricky, was now old enough to be put in the seat of the

Crouch #12 car. The usual Spring Green hype and spin was in place, and practice

had been held in the none-too-warm Vermont countryside. The youngest Crouch had

been a fixture at the tracks since he was old enough to be allowed in the pits.

Vociferous and fair-haired, the younger Crouch was not a lot like his famous

brother, but he was well loved by the Catamount community.

Preparations for the race weekend were pretty much complete. The

out-of-town teams either retired to a motel or to some generous local's garage

to make final preps on the car. The locals headed home or to the headquarters of

the racing team. Radio talk shows buzzed away; parties were held - so, about

every racing topic was covered at one point or another. Expectation was high....

and that included the Ricky debut.

Then, the following morning, the most unbelievable news began to seep

around. Ricky Crouch had somehow gone off the interstate in his father's pickup,

and was killed. The usually merry pre-race activity in the Catamount pits was

severely tempered by this news. People went through the motions numbly, sadly.

The race community was heartened to see the yellow #12 Chevy towed into

the pits - the car that was to be Ricky's. It was learned that former mini

stocker Tom Glaser, a friend of the Crouch family, was to try driving the car,

one that was somewhat familiar to him. To make a long story short, Hollywood

could not have made a better script. Glaser ended up upsetting the entire field

and winning the race - for C.A., Robbie, and Ricky. There wasn't a dry eye in

Victory Lane – or, for that matter, in the grandstands.

The most fun story of the lot is the one about the first race

of 1970, when two situations collided at Catamount’s Spring Green weekend: the

debut of the high – financed Little John Rosati Ford Fairlane team, and the

return to racing of Orange, Vermont’s unforgettable Chester T. Woods. The Rosati

team, with two matching Fred Rosner – built 1967 Fords, matching haulers, and

smartly uniformed crew, had the happenstance to park all that about next door to

Wood, and his horrible – looking 1962 Plymouth.

Chester

T. Wood, with his

unbelievable 1962 Plymouth. [Courtesy of Andy Boright]

The Agawam, Massachusetts – based Rosati bunch eyed Wood, his horrendous yellow car with the homemade lettering, and his crew member, tractor mechanic Calvin Frost, with bemusement. The Vermonters, too, did not know what to make of the spectacle beside them. A teenaged Steve McKnight, a Barre native and one familiar with Chester T. Wood, tried to suggest that no one in the Rosati pits better get too far ahead of themselves.

The Rosatis used every bit of

warm-up and practice time, coming into the pits and going back out under the

frowning, thoughtful eyes of Rosati, Sr., Rosner, and a battery of stopwatches

and such. Chet and Calvin weren’t interested in much of that practicin’ - wasted

a lot of gas, they thought. The man who had once plugged a radiator leak with a

Thunder Road hot dog and then had gone on to win the feature appeared more

interested in all the doo-dads in the Rosati pits next door [when he could see

them through the mobs gathered to watch Rosner’s every move]. Calvin, as I

remember, did change two plugs which he pronounced as lookin’ a bit “ratty”.

The preliminary races were run off with a lot of fanfare

given to the important new team from Massachusetts and with considerable

emphasis on the raging rivalry between hometown Bob Dragon and the hated Cabana.

There was also the newly-introduced automatic transmission Hurricane division.

So, neither Rosati’s nor Wood’s progress in their heats were all that noted.

Catamount had done away with its traditional “Freshman Reception”, a race for

all the rookies that year; so Rosati would not have a chance to outshine his

less-financed rookie rivals just then. But, both men qualified for the feature.

The high - profile Rosati team, at Catamount, a

year after that fateful first event with Chester T. [Ladabouche Photo]

The rest is almost as predictable as baby Bush invading Iraq. Little John struggled his way through the main event, finishing considerably behind Chester T. Wood’s top three finish. When Wood brought the rusty, dented yellow Plymouth into the pits after the feature, he and Frost were met with incredulous stares of begrudging admiration from the Massachusetts crew. It didn’t take Wood long to clear out after either - not much to pack and relatively few visitors to his pit area. They were long gone with the still - steaming Plymouth before the crowd around the Rosati car was anywhere near to dissipating.

Some very quiet words had passed between Chester T. and one of the Rosati crew, in the midst of all that chaos - and the Rosati car steadily improved to become a considerable force that summer. And they were very personable and popular all that summer. Nobody knows what was said, but it was pretty obvious what was thought - just by the looks on the faces of the men in the nice uniforms from South of the Vermont border. The locals ? Well most of ‘em knew better than to ever underestimate Chester T. Wood.

The last story is not a long one, but it goes under the category of poetic justice. The last race at Catamount was, in many ways, uncomfortable for the longstanding faithful Catamount fan. It was the last real race; local hero Beaver Dragon had suffered a terrible wreck at the track that day; and the final [and forever] track speed record had been set by an outsider, Russ Urlin out of Canada. Fans were looking for something to feel good about besides grabbing a chunk of asphalt or a piece of paint that might have been flaking off the grandstands for souvenirs.

Jean-Paul Cabana with the car

he won the first Catamount race with in

1965. [Courtesy of Cho Lee]

As it turned out, most of them got their wish. The last real race at Catamount was won by Jean-Paul Cabana. Even though many of the competitors that day were unfamiliar, driving those unfamiliar ACT plastic-bodies cars, the winner was the man who had also won the very first race Catamount ever had. Cabana, had – for the most part – been with Catamount most of its lifetime. For him to win, even if a fan usually booed him, seemed like the perfect way for the doomed track to go out. Despite the fact the track would end with a stupid enduro, the Cabana moment is what stands.

Return

to the Main Page

Return to the Main News Page

Return to the Columns Link Page

Return to the All Links Page